Casino Capitalism just managed to make the war in Ukraine much worse…

On the 24th of February, as Russia invaded Ukraine (the sixth-largest exporter of wheat), millions of customers rushed to supermarkets in a bid to store grain-based products, expecting a massive shortage.

At the same time, investors rushed to the wheat futures market to do what they do best; excessively betting against one another (completely decoupled from the market fundamentals of supply and demand) and exacerbating the problem to previously unheard-of levels, to the extent that grain elevators in the US are refusing to buy grains from farmers anymore, due to disturbance in financial markets. In other words, farmers in the US with perfectly fine and very much demanded grains, are not able to store and sell them due to excessive betting!

But before we jump into the dynamics of how this very bizarre situation (which even contradicts the basic principles of the efficient market theory) came to happen, we need to understand what are futures contracts, why they are essential to a functioning market, and how the recent deregulations lead to its decoupling from reality.

🧭 What Are Futures Contracts?

Futures are formally defined as contracts, that can be publically exchanged, and that allow you to buy an asset or a commodity at a fixed price on a future date.

Imagine the following scenario. You are a farmer who plans on growing wheat in autumn to later harvest and sell it in summer. You are basically planning to undergo an investment both of your time and money, hoping to see future profits in summer, but you have no idea how will the prices look like by then, so how can you plan ahead?

One approach is to find a miller, who also wants to plan ahead of his operations in summer and offer to deliver the crop on the 30th of August for the price of $5 per bushel, regardless of the actual market price by then. This is called a forward contract.

However, in a big market, you do not want to go searching for a miller before every season. To facilitate this process, you can offer your contract publically in an exchange for all the millers of the world, who can then flexibly resell it before its expiration date. This is called a futures contract.

The exchange here functions as a mediator between the parties; ensuring the quality of the grain, facilitating delivery and storage, as well as ensuring the enforceability of the contract against both frauds and liquidity situations. In other words, it becomes the buyer of every seller and seller of every buyer.

🏪 How Futures Market Actually Works

It is important to note though that in the real world due to the globalized nature of the exchanges and to avoid high delivery costs, most market participants do not use futures contracts for the actual exchange of goods, but rather as a financial tool to offset (hedge) any potential losses that may incur when goods are exchanged in the local market.

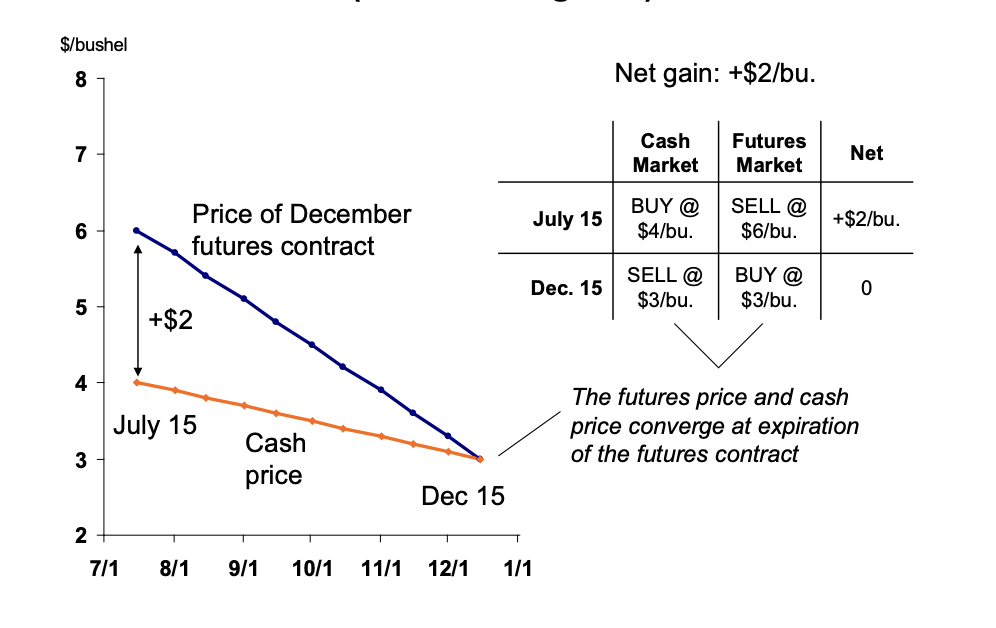

This last point is best explained by the example given in the Senate report of 2009 covering the effects of excessive speculation on the wheat market,

In the scenario shown in the graph above, a grain elevator would buy wheat from local farmers at the price of $4 per bushel and at the same time would sell a futures contract on the exchange offering bushels in December at the price of $6, netting profit of $2 per bushel.

When December comes, the price of wheat drops to $3. The elevator sells the grain to a local grain processor at the market price and at the same time before the expiration of the futures contract buys another contract at the same price of $3. This way the total profit of the elevator is $2 per bushel as if the corp was physically sold on the futures market without having to incur the delivery costs.

🌡 The Problem With Futures Market

It is indeed this property of futures contract to converge to the current market price (also known as spot price or cash price) of the commodity just around the contract’s expiration date that makes it an essential tool for the economy because it allows buyers and sellers of commodities to hedge against future losses as well as allowing them to reference the futures market when pricing their products.

This property should be guaranteed by the “Efficient Market Theory” which hypothesizes that if there would be a difference between the futures price and spot price near the expiration date, then enough people would exploit that by buying the product at the cheaper market and selling it at the more expensive one, netting a riskless profit, pushing the prices to converge.

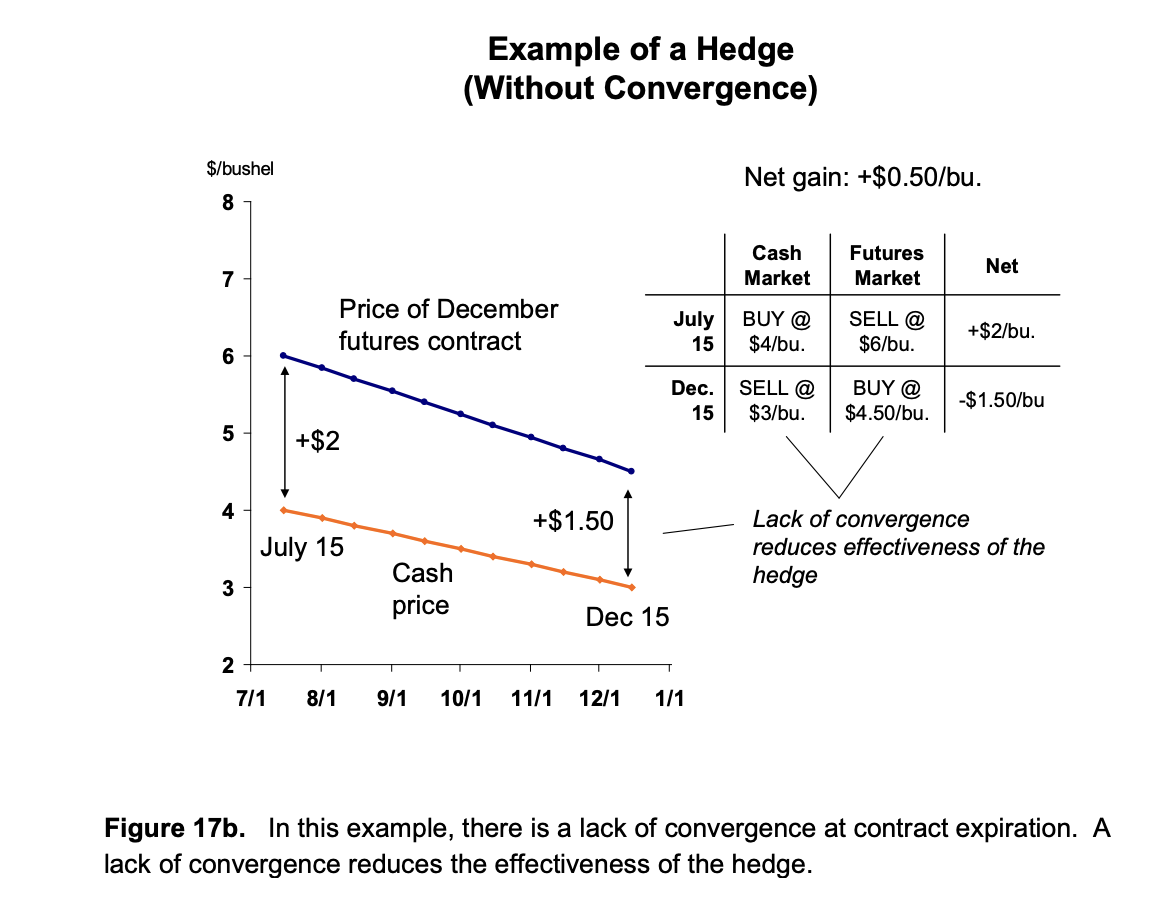

Unfortunately though when a market is dominated by speculators, who do not exchange any physical products, what gets exchanged instead is something called “shipping certificates”. These certificates are there to guarantee that the speculator can get the underlying asset on demand and can only be issued by a limited number of firms, limiting the possibility of arbitrage and pushing the prices to diverge.

If you think of the market as a decentralized computer that takes in all the variables and reflects them in the price to ensure maximum efficiency in resource allocation. Then excessive speculation is like a very strong noise signal that renders the computation useless!

This divergence is exactly what caused grain elevators to stop buying from farmers even in such times of high demand because their hedging strategy can not work anymore in such a broken market as you can see in the figure below. In other words, excessive speculation renders the futures market useless as market players can neither use it to hedge nor to discover a fair price for their products.

🐎 The Current Wild Wild West

A healthy futures market includes producers and consumers of commodities, and traditional speculators. Despite the negative connotation of the word “speculation”, speculators are essential for the market as they provide much-needed liquidity. If you are a farmer wanting to offer your bushels for sale in December, you do not want to wait till a miller shows up and buys the contract. Speculators facilitate the process of buying and selling, making the market more liquid.

The problem appears, however, when excessive speculation comes into place. This happens when the majority of market participants in the exchange are speculators rather than producers or consumers, pushing the market to be more and more decoupled from the fundamentals of supply and demand.

So how did we end up here?

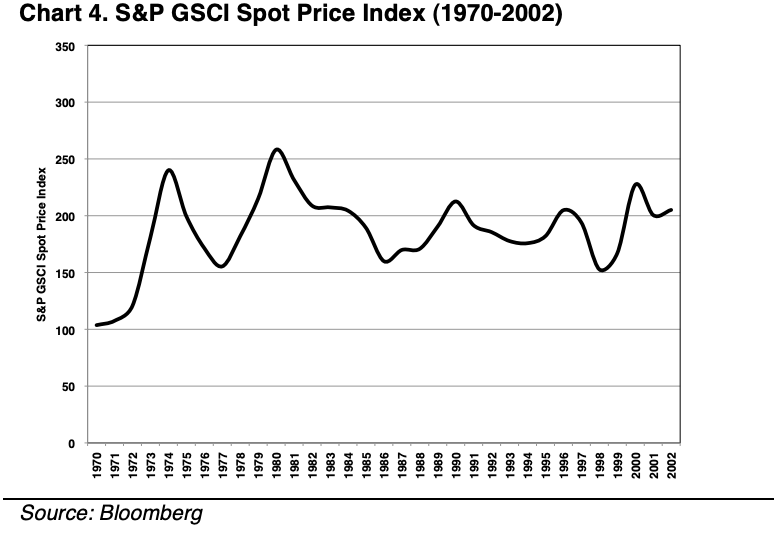

This problem was already well understood a century ago through the Grain Futures Act of 1922, which imposed position limits on speculators to prevent creating a chaotic environment for farmers and consumers. This was then followed by the Commodity Exchange Act of 1936 and finally the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) was born in 1974. All of this led to fairly stable commodity prices from 1970 till 2002.

Unfortunately starting from the 1980s a wave of deregulation measures started taking place that was eventually crowned with the Commodity Futures Modernization Act in 2000, explicitly preventing the CFTC from regulating the market.

A study by the Lehman Brothers investment bank, before it went bankrupt in the financial crisis of 2008, showed that the volume of index fund speculation has increased by 1,900% from $13 billion in 2003 to $260 billion in March 2008.

The effects of these measures were not immediately felt in commodities as investors back then were still drunk on the subprime mortgages. But with the financial crisis of 2008, swap dealers (Wall Street banks) managed to convince pension funds, hedge funds, and other investors that investing in commodity indices like the S&P GSCI guarantees “stock-like returns” while providing a hedge against inflation, which led to billions of dollars flowing into the market.

Unfortunately despite expert testimonies in Congress, multiple senate reports, and four attempts by the CFTC to impose position limits rules, the situation now does not look much better than it was in 2008. The recently passed vote on the final rule to enact the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, leaves the regulation power in the hands of the exchanges themselves. In the words of Commissioner Dan Berkovitz, “The proposed rule demoted the Commission from head coach to Monday-morning quarterback”.

This unregulated speculation has led to the unprecedented situations like in April 2020, where just one speculator owned 25% of all the WTI Crude Oil futures contracts, pushing the price into the negative territory or currently with the consistent divergence of futures and spot prices in the wheat market exacerbating the effects of the war in Ukraine.

We already have a precedent in 2008, where excessive speculation in commodities led to a meteoric rise in the prices of wheat, corn, and soybean, pushing 120 million additional people into poverty. Back then the world was neither struggling with a global pandemic nor with a war between the world’s largest exporters of wheat. Only God knows how many millions will have to suffer this time as well…

PS: If you believe that the increase in prices is actually caused by real supply and demand issues, I would recommend you read the amazing paper by Ke Tang et al. on the topic. They basically show how starting from the 2000s indexed commodities show a high correlation in prices (they all increase at the same time decoupled from the market) and how unindexed still behave normally. There are also a lot of papers showing the effects of speculations on the market.